The Utility of a Demanding God

Modernity loves comfort. It thrives on the ideal of effortlessness, a curated reality where everything is secularised, smoothed, and—above all—convenient. We surround ourselves with technologies and ideologies designed to make our lives less demanding, less engaging and less meaningful. But in doing so, we’ve hollowed out one of the most essential aspects of existence: the struggle to transcend ourselves. Nowhere is this more evident than in our relationship—or lack thereof—with God.

A God that demands something of you is an affront to the modern sensibility. A God that asks you to submit, to sacrifice, to become someone other than who you are right now? That’s an existential inconvenience, and it’s precisely why this type of God is so viscerally rejected by those who claim no faith. For many, the mere suggestion of accountability to a higher power feels like an insult, an assault on their autonomy. But this discomfort is where the true utility of a demanding God lies.

The Feel Good God and the Cult of Comfort

Consider the modern “feel good” God—a vague, feel-good entity who asks nothing of you. This God tells you to “follow your heart,” “live your truth,” and “do whatever makes you happy.” There’s no standard here, no moral objectivity, no accountability. Just a divine rubber stamp on whatever you already wanted to do. This God is easy to love because it never challenges you. It lets you remain precisely as you are, indulging every whim, ignoring every fault, it will lead you as easily into destruction as it will anywhere else.

But let’s be honest: this kind of God is useless. It’s a spiritual placebo, offering comfort without transformation, affirmation without growth. It’s the theological equivalent of an empty calorie—momentarily satisfying but ultimately unfulfilling. And the proof is in the fruits: a culture awash in anxiety, despair, and existential aimlessness, despite its supposed freedom from the “oppression” of religion.

We crave meaning, yet we resist the very things that provide it: struggle, sacrifice, accountability, community. A God who demands nothing from you doesn’t provoke resistance because it doesn’t provoke anything at all. It’s a vanity object reflecting your own desires back at you, nothing more.

Why Atheists Hate the Demanding God

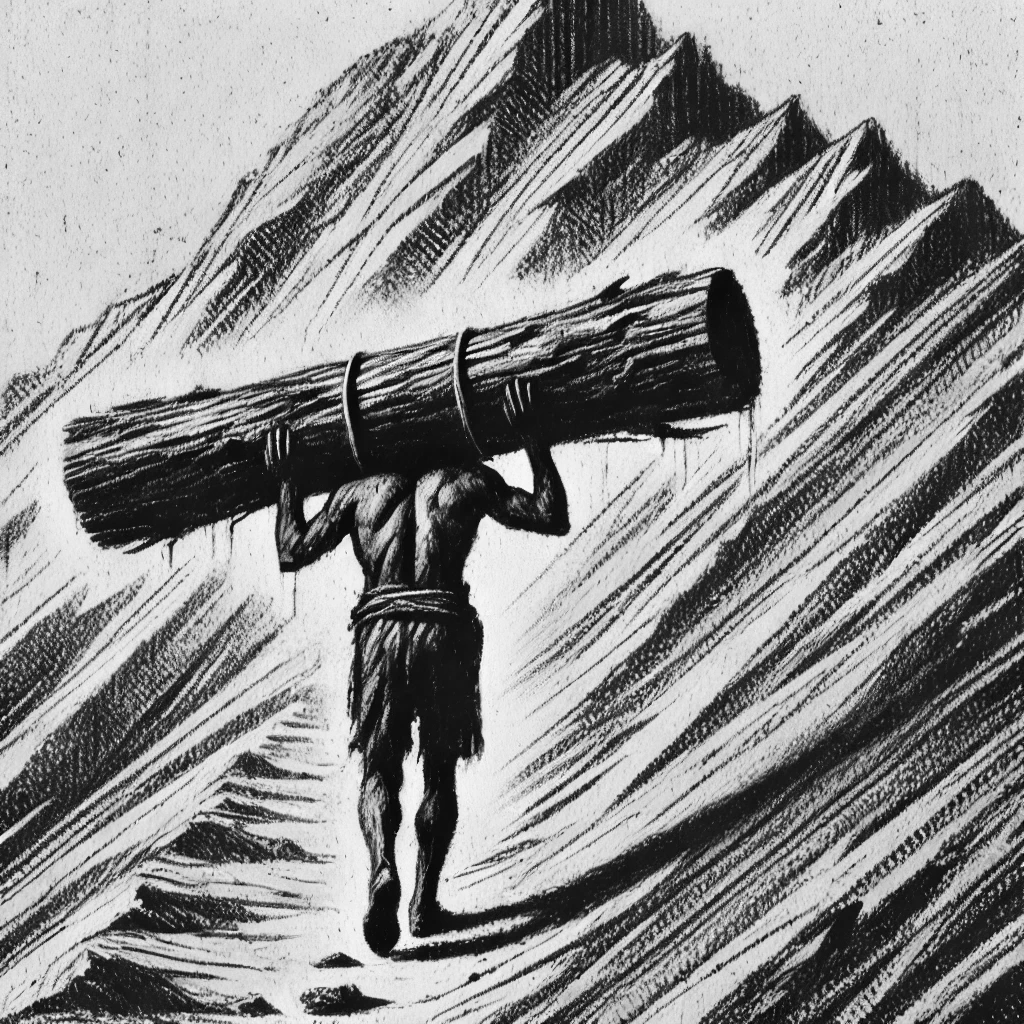

Now let’s pivot to the God who demands something of you—a God who says, “Pick up your cross,” or “Love your enemies,” or “Die to yourself.” This is a God that makes people squirm. A God like this doesn’t just sit quietly in the background of your life, nodding approvingly at every decision. No, this God is invasive. He calls you out. He looks into the depths of your soul, sees every weakness and failure, and says, “You’re capable of more—but only if you lean on me enough to change.”

Atheists, perhaps more than anyone else, find this kind of God intolerable. Their rejection isn’t just intellectual; it’s visceral. Because a demanding God challenges the foundation of their worldview: the belief that they are the ultimate authority in their lives. For many atheists, the idea of God is offensive precisely because it implies accountability to something greater than themselves. It’s not just the existence of God they reject—it’s the audacity of being told what to do by anyone or anything.

Ironically, the most vocal atheists often need God more than anyone else. Their discomfort with a demanding God reveals a deeper truth: they’re deeply invested in the universe being free of anything that challenges their sense of control or questions their behaviour. They scoff at the idea of divine judgment but obsess over scientific law and theory as if they’re sacrosanct. They reject faith while placing blind trust in their own limited, consensus based, ever changing perceptions of reality. It’s a rebellion born not of reason, but of fear—a fear that if they’re wrong, their entire sense of control collapses under the weight of transcendent accountability.

The Madness of Infinite Possibilities

Let’s take this further. At the heart of every worldview—whether religious, scientific, or philosophical—is a terrible truth: what we think we know is entirely provisional. The scope of our ignorance is unfathomably vast, and nowhere is this more profound than in our assumptions about the universe’s structure and purpose. Is the universe a vast narrative structure unfolding and teeming with meaning? Is it a chaotic sprawl of entirely random events? We can’t know for certain, and yet our choices about what to believe profoundly shape how we live, what we cultivate and the legacies we leave.

The modern mind clings to the idea that the universe is orderly, consistent, and ultimately knowable. This modern mind knows the measure of everything and the meaning of nothing. It’s heavily tainted by the bias of anthropocentrism. It insists that reality must adhere to laws we can study and systems we can comprehend. But why should this be true? Isn’t the assumption of a comprehensible system just as extraordinary—and faith-based—as the idea of an inscrutable construct? We lean into the former not because it’s inherently more plausible, but because it’s more comforting. Order provides a sense of control, and control gives the illusion of mastery.

And yet, epistemological humility requires us to pause and recognize the limits of our understanding. The deeper we peer into the mysteries of the cosmos, the more questions arise. Science, for all its rigor, ultimately gestures toward horizons it cannot cross. Questions of origin, purpose, and ultimate meaning remain beyond its grasp. In this light, the loudest atheistic denials of God are no more rational than the theist’s belief in a divine creator. Both rest on unprovable assumptions: one assumes a cold, indifferent universe, while the other dares to suppose a story—one with plot and purpose.

Here’s the critical distinction: embracing the possibility of a narrative framework isn’t just a theological exercise in futility; it’s a choice with real consequences. To live as though the universe has meaning is to orient oneself toward ideals that have historically contributed to human flourishing. Concepts like justice, mercy, sacrifice, and love don’t arise in a vacuum—they emerge from a belief that there’s a higher order, something worth striving toward. This belief has stabilized societies, inspired progress, and averted destruction, precisely because it raises the stakes of our existential gambit in an engaging way.

On the other hand, to deny any overarching framework—to insist that the universe is purely random—is to flirt with nihilism. Without a narrative, there’s no reason to strive for anything beyond self-interest. History shows us where this road leads: chaos, fragmentation, and despair. The absence of meaning doesn’t liberate us; it leaves us adrift, disconnected from the ideals that sustain civilization.

Epistemological humility shouldn’t mean rejecting narrative framework entirely—it means acknowledging that we can’t fully know its contours while still choosing to live as though it exists. This choice isn’t about proving or disproving God; it’s about orienting ourselves toward something greater, something that calls us to transcend our base instincts and build a world worth living in.

In the end, the universe’s narrative—or lack thereof—may be beyond our comprehension. But the choice to believe in one isn’t just a leap of faith; it’s a foundation for meaning, morality, and progress. And in a world teetering on the edge of chaos, that choice may be the most important one we can make.

Why Demands Create Meaning

A God who demands something of you cuts through the chaos and the excuses. He offers not just a framework for understanding reality, but a purpose for existing within it. By asking you to rise above your basest instincts, to sacrifice your immediate desires for something greater, He gives your life purpose and direction. This isn’t just about morality—it’s about the meaning that drives it. There is no morality without meaning. If your choices don’t mean anything, then your morals don’t matter.

The most profound truths are often the hardest to accept because they require you to confront your own limitations. A demanding God forces you to face uncomfortable truths about yourself: your pride, your selfishness, your fear of change. He doesn’t let you hide behind excuses or distractions. He calls you to step into the fire of transformation, to become more than you thought you could be. And in doing so, He offers something no amount of self-help or secular philosophy can provide: a reason to keep going when life gets hard and a deeply compassionate ideal to aim for.

The Dichotomy of Despair

Here’s the dichotomy: a theist who loses their faith in God experiences despair and meaninglessness, but an atheist who discovers God experiences something far more disruptive. The theist mourns the loss of meaning; the atheist is forced to grapple with the fact that they’ve been running from it their entire lives. A theist without God faces the existential reckoning of the void. An atheist confronted with God faces instantaneous divine judgement.

That’s why the loudest atheists often seem the most defensive. They’ve built their lives on the assumption that there is no higher power, no ultimate accountability. But deep down, they know it’s a gamble. And if they’re wrong? That’s not just despair—it’s an existential meltdown.

Conclusion: The Hard Road Worth Walking

A God who demands something of you isn’t just a theological concept—it’s a moral necessity. Without that demand, there’s no friction, no growth, no meaning, no obligation, no alignment. Life becomes a series of empty pleasures, fleeting distractions, market driven decisions, a profoundly hollow existence masquerading as freedom.

The modern world is desperate for meaning, yet terrified of the sacrifice it requires. But the truth is, a God who demands something of you is the only kind of God worth following. Because a God who asks nothing offers nothing. And a life without demands is a life without purpose.

So, pick up your cross. Step into the fire. Embrace the challenge. It’s not easy, but it’s worth it. Because in the end, the struggle to transcend yourself is what makes life worth living and what makes you an inherently redeemable and worthwhile creature.